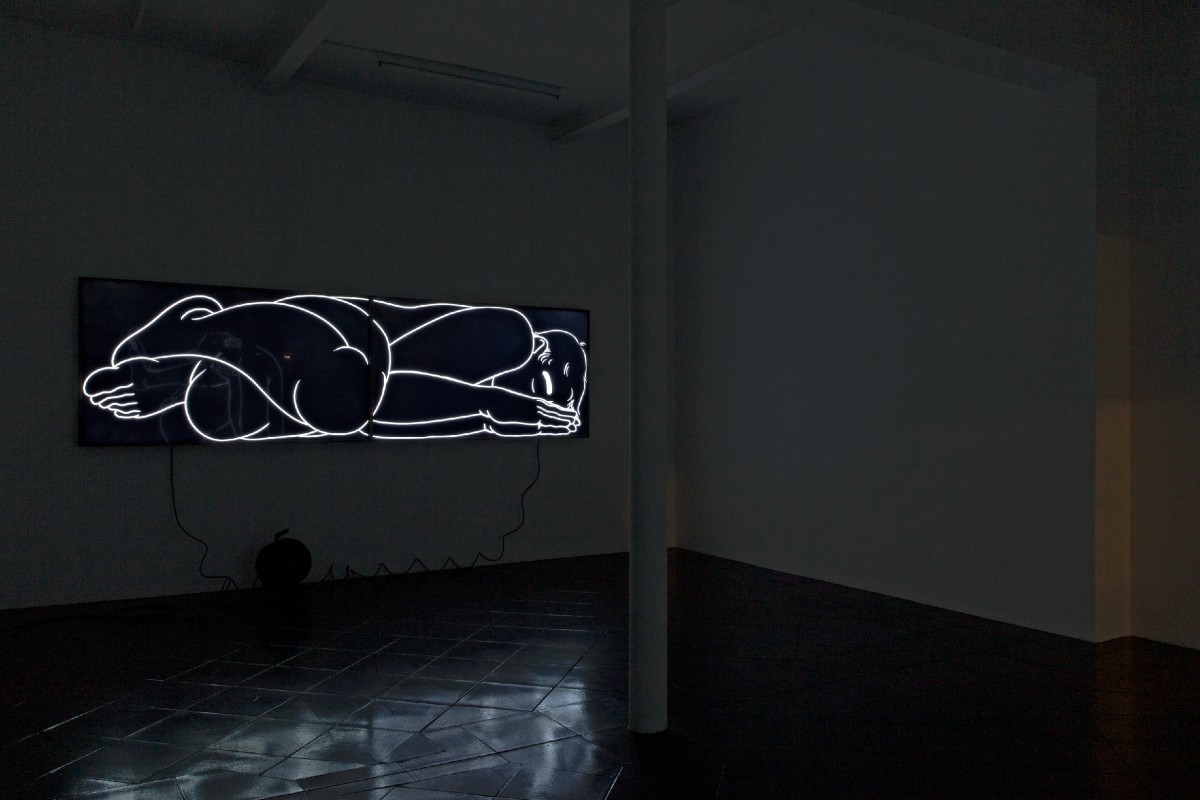

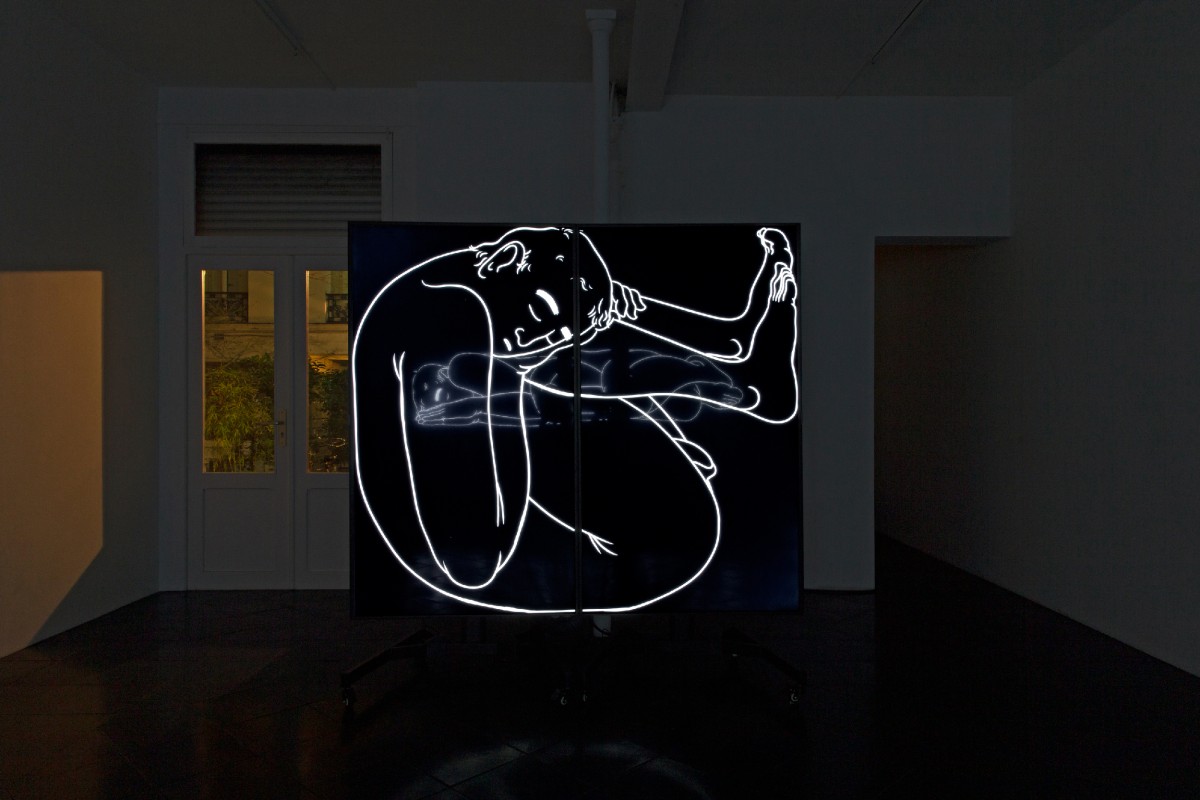

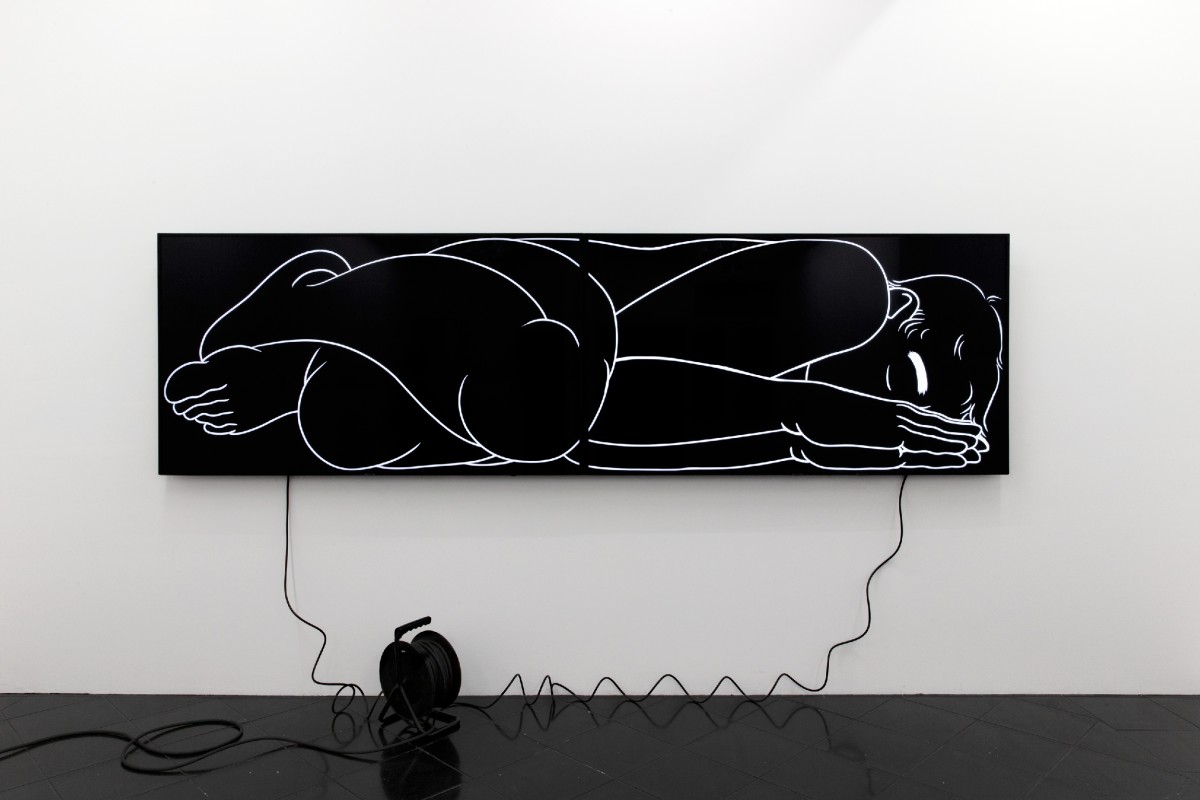

Imagine that the inner struggle with lust, love, loneliness and bottomless despair of the troubled adolescents in Dennis Cooper’s novels – George Miles, Ziggy or Larry – would come to life three-dimensionally. In Özgür Kar’s exhibition, Watching the world work against them(1), two naked and comatose male characters crouch with shining white outlines incarcerated in colossal black abyss-like screens. Their private fragility at the mercy of the voyeuristic gaze becomes the pitifully humiliated heart of the show. Despite their superhuman size, a kind of “obduracy” camouflages these characters in their solitudinous delirium as something “vulnerably small” that, to the contrary, show themselves to be almost aggressively transcendent through the ever-looping murmur of their canned phrases: “Fuck you! no! I’m being real! I’m true to myself! I’ll always be me! you do you, I do me!”

Unlike Jean Genet’s Lieutenant Seblon, and his unbridled desire for «untouchable» Querelle, where tenderness appears as aggressive hardness and potency – steel, weapon, muscle, penis – until Seblon “makes” Querelle soft and yielding, Kar’s characters don’t even direct tenderness at one another. Instead, they direct tenderness towards the self, culminating in an absolute loneliness, inner omnipotence that never softens. This is a form of potency that exorcizes the other through seduction, the other as eros, the other as pain. It is a way of speaking from the injured soul of an abandoned child who hatches gruesome plans of revenge in defiant rage – where every wish in the imaginary creates at the same time a zone of unbounded despotism. It is a way of letting all others, all the gods and chains of restraint, lick its ass and drown without resonance. Kar’s characters could be mere shards of a fractured «I», a pervasive alter ego, a so-called ordinary person that generates a site for storing the self. As Rimbaud described it, «J’ est un autre» (I is another), a banned other.

The bow of the violin hasn’t moved, yet music emanates from it. Another character plays it, while he automatically produces the tones as if they are instilled in him. For Kar’s characters, such a performance means being trapped in the modern rosary, a portable confessional screen for self-monitoring. They excrete the sound that binge-watching and pathological surfing have left: tatters of Soap and reality TV, video sharing platforms, pop songs. Their laconic extremity could have descended from one of Pettibon’s disturbing black and white assemblages of failed promises. They have hardly any language of their own anymore.

Watching and listening to them also means being enraptured, a seeker, without any landmarks. Like the characters, we are at the mercy of a subjective world of puzzlement that threatens to overwhelm us too. It is as if the narrative space is constantly “under construction.” In Mieke Bal’s words, “exposition,“ within the semantic and actual space, here becomes a speech act that conveys a text to which the viewer is complicit.

Kar’s semiotics might be the narcissistic revenge of the imagination of a reality that is mediated, refabricated, clinged to and stitched, day in day out, as digital mirages. They enter our private cinematic psyches and extend the mind to seductive and terrifying realms, while relentlessly particularizing the ego. Ultimately the self becomes imprisoned in the finitude of its assets; or even, as in the case of de Sade, literally imprisoned 24/7, in order to cultivate the virtue of language, and discover its insufficiency, that it is never enough and usually fails.

1 Dennis Cooper: My loose Thread, Edinburgh 2002.

Elisa R. Linn

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>